So as you’re likely aware my last two attempts to actually climb to the summit of Mount Everest in Nepal have fallen tragically short after being caught up in the two consecutive biggest disasters on Everest in as many years, this year narrowly escaping the several avalanches in the Khumbu Icefall triggered by the Nepal earthquake. I returned home wondering why I had been spared when three of our team at base camp had been so cruelly taken, resolving to do what I could to help them and others less fortunate.

Living in the leafy flatness of Cheshire, endurance cycling has always been the key part of my training for mountaineering expeditions. Within a day or two of arriving home I went back to my notepad and came up with crazy fundraising ideas. Eager research uncovered a concept known as ‘Everesting’, cycling the height of Everest in less than 24 hours. Why, you ask? Because it’s there? I needed to summit something. At the time of reading this new trend had been completed by less than two hundred worldwide. This style of Everest ascent would keep me safe from avalanches, but could potentially maim me in the process. Semi-professional cyclists had described it as bloody hard, many had said it wasn’t their cup of tea, and others had failed. Who was I to follow suit? Considering the link with Everest and the potential to raise a lot for charity, I would give it a go anyway, and hopped straight back on the bike without the post-expedition rest I needed.

The date was put back three times as I encountered chest infections and better understood how hard this was going to be. On announcing my plans, one person warned me I would have only a 50% chance of survival. Was this sensible? Of course not. But as a young and conditioned athlete completing a number of big endurance events, I quickly dismissed this. Once sponsorship started to be pledged, I knew that there was no way I would back out anyway. The training was taking away crucial time I needed to focus on other aspects of my life, so I was glad to get it out of the way- 6th August was set in the calendar.

Conversely, I started working at YHA Windermere, so lived in the Lake District with Kirkstone Pass on my doorstep. I was training every other day, sometimes three in a row, but to prepare for a huge event in a very short time period the intensity was relentless. I regularly struggled on ‘The Struggle”, a 20% gradient road from Ambleside, making continuous reps for several hours to the amusement of cars and tooting motorcyclists. I lost nearly half a stone in weight and couldn’t let the fitness go to waste. Resultantly, my fitness has peaked at an all time best with a resting heart rate of 40bpm, and if I maintain it for my Aconcagua expedition in November, I’ll be in a very good position indeed.

The day earlier I headed up on the train to Appleby with my good friend and fellow keen cyclist, Ste Rumbelow. We checked in to YHA Dufton, a cosy little hostel on the edge of the Pennines in the Eden District. The target for my Everesting was eventually agreed to be Great Dun Fell. It had already been ‘Everested’, but being a private road it lacked the traffic, and the superb road surface trumped the potholed and corrugated tarmac of Kirkstone Pass many times over. Great Dun is widely known as the British Mont Ventoux, with a whopping 632 metres of ascent per climb. Psychologically, it seemed more tolerable to make fourteen and a bit ascents than counting down from a hundred to hit the required elevation. It was a fragile balance; too gradual a climb, and you’d rack up much bigger mileage, whilst too steep a climb, and you risk burning your quads to smithereens before you get to the ‘Death Zone’, which begins above 8000m altitude on Everest itself. We could see it from the hostel too. A few expletives followed.

Whilst sorting out gear we met Mick Walker, a cyclist friend from Yorkshire. Mick is an inspiration- entirely vegan and actively promoting a healthy lifestyle through his diet and endurance cycling, in the same way I promote active lifestyles through my role at Active Cheshire. I was really glad to have him along.

It was an early night for a 4am alarm. ”I feel sorry for the poor buggers sharing the dorm with us” I remarked- without realising they were still inside.

A huge bowl of sugary Porridge started me off as usual and I held my nose as I gagged a shot of beetroot juice, with the nitrates proven to increase blood oxygen capability. For the first time since Camp 1 on Everest I was going completely caffeine free, as I didn’t want to put my heart under any further stress.

Ste and I cycled to the start for a 2 mile warm-up along reassuringly dry country lanes towards the village of Knock. This ‘Everest base camp’ had no tents, but Mick’s car, which would prove to be an absolute godsend. On that note, we parked up on the road near the Knock Christian Centre in the hope their faith would bring offerings of tea and biscuits in the freezing cold (and some vegan ones for Mick).

About 5:22am the clock started and we set off as a trio, ticking off the first two ascents quite quickly. The first was hard, the second much more reassuring once our legs had woken up. Mick was keen to go for the summit too which was great- I originally hadn’t anticipated the others would be mad enough to follow me but the thought of us becoming the youngest and oldest ‘Everesters’ in one day was quite special. Ste had already conspired that with his 25-t cassette on the back gears (opposed to our 32-t) that he wouldn’t be going for the top. Either way I was very grateful to have their support. Great Dun Fell is actually home to a radar/communications station shaped curiously like a giant golf ball, hence the tarmac road all the way to it’s summit for 4.6 miles. The Pennine Way trail also joins part of the route. It’s a beautifully bleak part of the world as the road winds it’s way up through forests, farmland, streams, grey outcrops and grassy hills along the edge of a seemingly never-ending valley. Spotting Barn Owls and Red Squirrels on a number of occasions lifted the spirits too.

Each ascent was estimated to take about 50 minutes, with a maximum 3 minutes on the top for stretching and a quick sponsor photo, whilst the descent took about 15 minutes, so about 1 hour 10 minutes in total. Unavoidably this schedule was a bit optimistic. Time slips away no matter how organised you are. We didn’t hang round to admire the view- not that we had much anyway. Back at base camp, Ste hung around to rest his legs and brew hot chocolate, whilst posting tweets and updates. From the 2nd ascent, I was taking on about 50g of carbs per hour during my breaks, with a variety of fats and protein to prevent nausea, provide variation and prevent muscle wastage. I didn’t know how hard it would be, but in future I would definitely bring less fuel.

If you’d like to give your dentist a nervous breakdown, try the ‘sea food diet’ below, which is roughly what I consumed during the event itself…

– 4 x garlic herb bagels (1 plain, 1 with peanut butter, 2 with sliced cheddar cheese and houmous)

– About 200g Soreen Orange Malt loaf and 4 tbsp peanut butter

– 3 small cups Malteasers Hot Chocolate (for when it got REALLY serious)

– 1 x SIS Cherry and Vanilla carbohydrate bars

– 4 x SIS Isotonic carbohydrate drinks

– Approx 100g homemade flapjack

– 1 Banana

– Large handful dried Figs

– A few Maryland cookies

– Approx 7 litres of water in total

N.B. You sea the food… you eat it!

Mick and I continued heading up and down the route monotonously. As we got to know it, we dreaded the most painful bits, the occasional dips in the road that would elicit swearing at 30mph, the sharp hairpin bends and the sheep-infested areas. At base camp we would simply grab fuel, eat or bring it, re-layer as necessary and head straight back up before our legs stiffened up. Having Mick alongside for company was massively helpful, and provided a welcome distraction to speed up those first few painful hours so I could preserve focus for when I needed it later on. We moved at a similar pace, but I often dropped back to keep my heart rate below a max of 160bpm to prevent burning quads/onset of fatigue/keeling over. Even with the easiest cadence sometimes this was a bit ambitious. GDF has short but noticeable sections of 20% gradient, and if you spin too slowly, you can lose momentum and hit the deck.

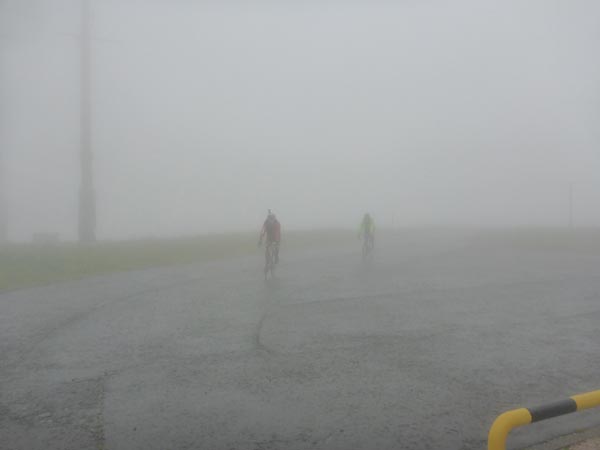

We were at the mercy of the Pennine weather. Helm winds rattled us, constant rain set in for a good 3 or 4 hours, and the cloud level plummeted so the claggy pea soup on the final hundred metres poured down to about halfway up the route. Psychologically it was actually comforting not being able to see the grinding twists and pulls of the route ahead. Ste joined us for another rep and waited at the summit shivering in his bobble hat. The descents were now increasingly perilous with wet brakes. Ste hit 46mph at one point, and subsequently nearly binned it on one corner, but I told him he wasn’t allowed to do so without wearing my GoPro. With sporadic fierce gusts in any direction threatening to sweep the wheels from beneath us we fell behind schedule even further. On the ascents we would be sweating heavily, yet shivering on the descents.

By about rep 6, we were soaked. Rain had hit base camp now too. I worried this may last all day- wet clothes are cold clothes, and hypothermia was a very real threat. We had to change completely. My friend Kate from Penrith, an Everest 2017 hopeful, had arrived to support so both Ste and Kate cycled to YHA Dufton to take clothes to the drying room. My brake pads had practically melted, spewing black tarry liquid all over my frame, and by the 7th rep- almost halfway point- it was time for a pit stop and re-charge of my Garmin. I took a moment to read the support I was getting online, which was absolutely phenomenal.

The heavens had retreated and we now had beautiful sunshine and calm winds. The iconic golf ball now taunted us on the hill at the other side of the valley. Keeping pedalling on the steep sections grew harder. We climb Everest as a team, and likewise, I wanted to remain together as long as possible on the bike. Mick selflessly insisted that I don’t hang back for him if we were moving at different paces, as he knew we had a big day still ahead. Kate joined us too and got some brilliant photos and video en-route of our efforts.

On the summit it was bitter to think that after 14,800ft and over 3400kcal burnt, I was still barely halfway. Once you hit half-way point- there’s just that wonderful minor psychological shift. From now on, I would count the number of reps left, as that was smaller than the ones we’d done.

Good nutrition and hydration kept our minds and legs strong. I worried about cramp or tendonitis, but neither came. The biggest risk now came from dehydration in the heat, or the sheep who ran startled into our paths on a number of occasions. Small barriers were the only thing stopping us veering off down the mountainside into the back of a rescue helicopter. Mick decided to rest after 8 reps. He knew his own limits. On this lone rep, number 9, it finally hit me that I had 6 and a bit left. This would take well into the early hours of the morning.

The sunlight began to fade, along with the temperature. I swore at my watch. Four to go. I was amazed at how strong my bike had been; barring the grease that was oozing out of the stem and headset. Ste joined me on number 11, albeit in chinos, a down jacket, and trainers, as we caught a wonderful panoramic sunset on the top. There was a long pull round a corner then a gentler final section to the summit after passing through another gate. I could feel my pulse in my ears, and it sounded erratic. I knew that some people had failed Everesting attempts due to atrial fibrillation- so my mind was probably playing tricks with me. ‘50% chance of survival’ repeated in my ears. My head throbbed and my chest felt tight, probably transferring from my sore shoulders, and I noticed my heart rate was much lower despite the same effort. Scientifically, this is actually due to the heart becoming more efficient/aware of what I’m doing, rather than a cause for concern. At least I hoped so. Each ascent was only a little bit slower although I’d stopped timing each one.

”Mate, I’m scared. Don’t think I can do this” I confided to Ste. ”You’ll be fine, you’re bossing it” he told me.

I had three to go as I got my head torch on. My legs were annoyingly fine having clocked up over 100 miles and 6,750m of ascent. Sadly Kate had to go home before the summit push. The pitch-black darkness wasn’t too bad. I kept my head down and played music on my iPod. There were no cars up here. Sheep eyes reflected back eerily in the darkness as I sung along to the music. I thought back to the training I’d done, and comforting thoughts of my bed less than 5 hours away. The day after I would be relaxing and finally able to put my feet up whilst I finished my book. My biggest concern now became my support team. I felt extremely guilty with Mick and Ste sat freezing in the car whilst I continued. I worried they may encourage me to call it a day as the night grew later; and I might not be able to resist. But they were superb, and knew that I had to finish this. Otherwise over 15 hours of pain had gone to waste. If I couldn’t climb Everest itself, failing to Everest on a bike would have crushed me. I didn’t want to be making excuses to all the people who had backed me why I had given up on the final hurdle.

Rep 12 done. Nearly midnight. I had 2 more. The fell tops were surprisingly calm, whilst a little eerie in the fog. Lights of the villages and towns twinkled below. The chaps had been snoring in the car until Ste came outside dreary-eyed to meet me and check the bike. I had texted my location at each gate for safety purposes. ”Stop worrying about us” he said, ushering me off again. Summit fever was kicking in, and gave me a final burst of energy as I neared the ‘death zone’, typically over 8,000m altitude on Everest.

”Are you guys ok if I go and knock this bastard off?” as I arrived back at base camp for the 13th time. It was nearly 1am. The final reps flew by as I fell into a trance. My body couldn’t fail now, as I urged it onwards. I collected the spare inner tubes and supplies I’d stashed along the route. Keeping the bike light was incredibly important, but now I didn’t care.

I expected to be pushing through agony, fighting screaming muscles, perhaps crying and having to give myself the Mr T treatment. I felt nothing but strength. The final steep sections were enjoyable because I knew it would be the last time. I crawled to the summit with a smile on my face. My Monty Python re-enactments had already started, which usually happens when I get bored during endurance events. I’d finished most of my EPIC7 challenges solo in the dark, so this was quite fitting. At 1:46am, I’d done it. I thumped the air. If it hadn’t been nearly 2am, I’d have called mum like I’d planned to on the actual Everest summit this year. Sadly, I had nobody to hear me shout ‘SUMMITTTTT!’ as I pulled up to the giant golf ball for the final time. But perhaps I did. I felt goosebumps prickle on my neck and arms, and remember clearly the feeling of somebody/something firmly touching my shoulder. Hallucinations are common in huge endurance events, but I didn’t feel the usual exhaustion. Nonetheless I got out of there promptly, humming the tune to Ghostbusters…

Like on Everest, I had to exercise care on the descents now I was ecstatic and tired. Arriving at base camp to a big man hug off them both, I was lost for words and thumped the handlebars proudly. I’d done it, and started to stagger around as they helped me into the car. At 3am I collapsed into the hostel bed with ravioli and a protein bar in rancid cycling lycra. I struggled to sleep. The next morning I was wide awake by 6am, still buzzing on adrenaline, with only mild soreness. Later that afternoon, the nausea, dehydration and loss of appetite would kick in as I finally crashed.

All we had left to survive was a train journey; screaming children testing our sleep-deprivation, legging it down platforms to catch connecting trains, being heckled by a train-spotter and other people insisting they had reserved our seats. They’re lucky I didn’t unleash the lycra…

Over £2,500 raised for Nepal now- enough to rebuild an average house- with HUGE thanks again to all who donated so generously. I am humbled. Especially to the following businesses and individuals who ‘sponsored’ an ascent by donating £100 or more- Chester Business Club, Westgrove Group, Vivio, Spring Coaching, Sharples Group, Click Consult, Veracity, Xpress Legal Services, Dan Hallett, Interim Performance Management x 2 and Kuoni Travel. If you’d kindly like to contribute to our efforts, any support is still greatly appreciated! www.justgiving.com/EPIC7

Lastly, but by no means least, I simply couldn’t have done this without a support team. I am hugely indebted to Mick and Ste for everything- especially staying out there till such an ungodly hour. Also to Kate, and the Edge Cycleworks for getting my bike into Everesting condition.

I may not have summited Everest (yet) but I’m delighted to join the elite ‘Everesting’ hall of fame, amongst fellow loonies. It’s all about adapting and overcoming to make a difference. Finding a way or making one. And the summary? Not the hardest thing I’ve done. Still, a superb hugely rewarding challenge that’s not for the faint hearted. Lots of commitment and preparation, a few screws loose, solid mental strength, vaseline, and tough legs are essential. Enter at your own peril. Life begins at the edge of our comfort zone.

GoPro movie coming soon- in the meantime, here’s some stats to whet your appetite, or view on Strava here>

– Distance cycled (including from hostel): 131.8 miles

– Height gain on Strava: 29,117ft- Everest is 29,035ft

– Cycling duration: 16:42 hours

– Elapsed time: 22:46 hours

– Calories burnt: 7007 kcal

– Average heart-rate: 128bpm

– Maximum heart rate: 169bpm

– Maximum speed: 38mph

– Flat tyres: 1- on Ste’s bike! Seriously?

– Crashes: Nearly…

– Brake pads wrecked: 2

– Sheep ran over: 0

– Screws lost: The toolbox

– Funds raised for people who need it: £2,540